How to Use This Tried-and-True Technique to Build Maximal Strength and Power

Steven Fleck shares his views on Classic Strength/Power Periodization, a tried-and-true technique to build maximum strength and power. When I'm approached in the gym, the question I'm most frequently asked about strength and power goes something like this:

"I've been training for some time now, and I've recently hit a plateau—how do I break through it and continue to maximize my strength and power?" Inevitability, the answer is, "I train every set to failure, to where I can't do any more repetitions." In other words, from my experiences, the vast majority of us are misunderstanding that in weight training failure equals intensity, so it doesn't really matter what weights or program we use. Much of the problem is likely due to the fact that, for years, we've all been duped (by the foolishness of the local "average" gym trainees) into believing that using the same weight-training program month after month, year after year, will somehow yield maximal strength and power gains forever. Not so. Therefore, my suggestion is a fundamental one: try some type of periodized resistance training to really "wake up" (or "shock") the muscles to reignite gains and build maximal strength and power.

TRAINING VARIATION IN PRACTICE

Experienced Olympic track and swimming coaches know the value of training variation in preparation for competition. Training variation is the reason these coaches have their athletes perform

different types of training sessions on

different days of the week and at

different times of the year. Years of feedback from their athletes as well as observation has taught them that

training variation is an important aspect of preparing their athletes for their best possible performances. Unfortunately, many of us have made the mistake of sticking to the exact same weight-training program for too long, complaining all the while because we aren't making any further gains in strength, power, muscle size, or definition. Perhaps we should wake up and learn something from track and swimming coaches! That is, the value of training variation to bring about continued, progressive long-term gains in physical fitness, aesthetics, and muscular performance. There are several variables that can be changed in a weight-training session that cause training variation, typically termed

acute training program variables. These variables include, but are certainly not limited to, the exercises performed, the exercise order, how many sets of each exercise are performed, how many repetitions per set are performed, and the rest in between sets and exercises. Changes… even slight changes, in

any of the acute training program variables will bring about a change in the training stress and potentially long-term adaptations, such as strength and size gains, caused by successive training sessions. There are virtually limitless combinations of the acute strength-training program variables. So, there is a virtually limitless number of different training sessions. Let me explain with a simple analogy: consider the number of digits there are in a phone number—ten—and see how many unique combinations can be created, without duplicating the same ten-digit number twice, by changing just one digit at a time. Surprisingly, the mathematical law of permutations states this would create approximately 3,628,800 different phone number combinations. Training is no different. Considering there are

at least ten acute training program variables we could change, changing one variable each workout would allow us to perform a total of over three million

different training sessions. Training variation is the reason these coaches have their athletes perform different types of training sessions on different days of the week and at different times of the year.

POWER PERIODIZATION IN TRAINING

Classic strength/power periodization focuses primarily on variation in training intensity and volume. Traditionally, intensity refers to the percent of one repetition maximum used in a training session. So the greatest intensity possible using this definition of training intensity is lifting as much as possible for one repetition or training using one RM (repetition maximum). However, practically speaking, intensity can also be gauged using repetition maximum weights. With this in mind, training doing six repetitions per set using six RM weights is

more intense than training doing 15 repetitions using 15 RM weights because six RM weights would be a greater percentage of the one RM. The fact is, training volume is really the amount of work performed. Two practical ways to estimate training volume are: 1) the total number of repetitions performed, or 2) the number of repetitions performed times the weight lifted. For example, if three sets of an exercise are performed for 10 repetitions using a weight of 100 lbs, then these two ways of estimating training volume would be equal to 30 repetitions performed and 300 total pounds lifted, respectively. Using these practical definitions of training intensity and volume, it's fairly easy to see that training at a very high intensity or high percentage of one RM cannot be performed with a high volume or for a high total number of repetitions. This simply means it's impossible to lift a true one RM of an exercise for lots of repetitions per training session. It is possible, however, to use a lower percentage of one RM and perform more repetitions per training session.

THE CLASSIC STRENGTH/POWER PERIODIZATION RELATIONSHIP

In my practice—working with Olympic athletes, or those aspiring to become Olympians—classic strength/power periodized weight-training programs are widely accepted, and because of that, they're followed by most strength/power athletes, such as Olympic weightlifters, shot putters, and track and field high jumpers and sprinters. For these athletes,

competitive success is in large part dependent on maximal or one RM strength/power. Although we may not be training to win a gold medal, the theory surrounding classic strength/power periodization stresses one must train in a manner that perpetually maximizes the one RM. With that in mind, one goal of this type of training program is to maximize or “peak” one RM strength/power in preparation for competition. (Or, better stated in our case, to break through a strength gain plateau.) In practical terms,

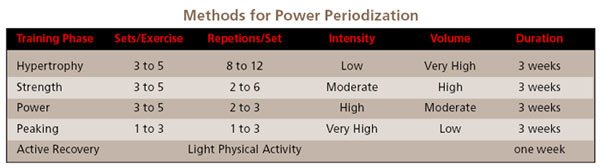

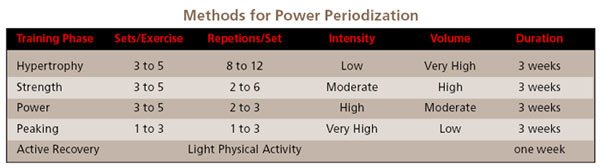

this is accomplished by initially training using low intensity and high volume. As illustrated in the chart below (entitled Methods for Power Periodization), as the training cycle progresses, intensity increases and volume decreases until intensity peaks and volume is at its lowest point in the training cycle. This final, or near final point, would coincidentally occur right before a major competition, where maximal strength/power needs to be maximized for the best possible performance.

CLASSIC STRENGTH/POWER PERIODIZATION TRAINING PHASES

Because we already know there is virtually an unlimited number of possible variations in the intensity and volume of training phases in a strength/power periodized training program—the training phases presented in this chart are just one of these possible variations. When put into practice, normally, the training phases are given a name—describing the major goal/outcome of the training phase—and they are three to six weeks in length. Let's review each of the phases, in more depth, to clearly understand how their application would yield a desired outcome: 1) HYPERTROPHY —the major goal of the hypertrophy phase is to maximize muscle size gains. The definition of hypertrophy is an increase in muscle size or the thickening of muscle tissue in response to stimuli, such as weight-training exercise. Generally higher training volumes do appear to have a greater influence on muscle hypertrophy increases. 2 and 3) STRENGTH and POWER —the major goals of these phases are to bring about maximal strength and power gains, respectively. Interestingly, the first measurable effect in strength and power is an increase in the neural drive stimulating muscle contraction. That's why, within just a few days, a person who is untrained (i.e., new to weight training) can achieve measurable strength gains—just because they're "learning" to use the muscle. In fact, he or she can continue to gain strength for a period of up to several months. Then it literally stops. At this stage, a neuromuscular adaptation has occurred and new stimuli are needed. 4) PEAKING —while the goal of the peaking phase is to maximize one RM strength/power, remember the goal of this training program is to maximize one RM or near one RM strength/power because the athletes who use this training program in large part are dependent on this characteristic for competitive success. Your goal when using this type of training program can be to increase your previous one RM best or break through a maximal strength plateau. 5) RECOVERY —after completion of all of the training phases, typically a short (one- to two-week) recovery phase is allowed where little or no resistance training takes place. If resistance training is performed in this training phase, it is of low-volume and low-intensity in nature. As an example, if each training phase were three weeks in length and the recovery phase were one week in length, completion of the entire training cycle would take 13 weeks.

AFTER RECOVERY—WHAT'S NEXT?

After the recovery phase, the entire training cycle would be repeated. This means that approximately four entire training cycles would be performed each year. Incidentally, however (and this is important!), due to increases in strength, each new entire training cycle beginning with the hypertrophy phase would start with higher weights for a particular number of repetitions of an exercise than the previous cycle. That is, any RM resistance of an exercise should be greater than in previous cycles because of strength improvements. Keep in mind, in all strength/power periodized training programs, the characteristic pattern of increasing intensity and decreasing volume are accomplished by performing greater numbers of repetitions per set in the initial training phases and gradually decreasing the number of repetitions per set as the training cycles progresses. Because the weights used in each training phase are true RM resistances or close to RM resistances for the number of repetitions performed per set, training intensity automatically increases as the training cycle progresses. Until in the peaking phase, true one RM or very close to true one RM repetitions are performed. This results in a maximizing of one RM strength/power at the end of the peaking phase.

THE FINAL ANALYSIS… STRENGTH/POWER PERIODIZATION

As with all training programs, I suggest the first question you should ask yourself is, "Does this training program work?" However, almost any reasonable weight-training program will result in increases in strength and muscle size. So, the next, better question you should ask yourself is, "Does this training program result in greater muscle size and strength gains than other types of training programs?" In the case of classic strength/power periodization, the answer to both of the above questions is yes. Anecdotally, most strength/power athletes use some form of periodized training. This indicates that these athletes believe this type of weight training does result in continued maximal strength gains. Additionally, the most recent American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand (2002) on resistance training concludes that virtually all individuals should use periodized resistance training once they have achieved a moderate training status. A professional literature review from Fleck as well as a meta-analysis (Rhea and Alderman 2004) also conclude that periodized resistance training results in greater maximal strength gains than non-varied resistance training programs. Upon closer inspection of one specific study from a leading physiology PhD (Willoughby 1993), which compared strength/power periodized training to non-varied programs, we can discern more about the strength response to periodized strength/power training. This study compared one RM strength gains due to strength/power periodized training to non-varied programs of six sets of eight repetitions and five sets of 10 repetitions in college-aged recreationally weight trained men. Bench press and squat one RM were tested every four weeks during 16 weeks of training. Looking at the bench press information presented in the chart below (entitled Bench Press and Squat), the periodized training resulted in significantly greater gains in one RM after eight weeks of training and continued to show greater and greater increases in one RM as the 16 weeks of training progressed. While the other two training programs did show significant increases in bench press ability, the increases were substantially smaller and at least for a portion of the study (four weeks to 12 weeks) showed what many people would call a "training plateau." Bear in mind, the men in the non-varied training programs were training hard: they were performing sets to near failure each and every training session.

META-ANALYSIS:

A meta-analysis is a statistical procedure where the results of all the studies examining a particular question, such as what weight-training programs bring about the greatest increases in maximal strength, can be collectively analyzed with a statistical procedure. This procedure results in a conclusion based in statistics and not merely on someone examining all the current information concerning a question and reaching an opinion on what all the information means. In other words, it's conclusive, based on objective measures, and is not left to subjective interpretations. Equally important, the one RM squat information also favored the periodized training program, but it took 16 weeks of training before the periodized program showed a significantly greater increase in squat ability over both of the non-varied training programs. For up to 12 weeks of training, the six sets of eight repetitions and the periodized training programs resulted in similar but significantly greater strength gains than the five sets of 10 repetitions. Again, all programs showed significant increases in strength; however, the pattern and magnitude of strength gains were quite different between the bench press and the squat. The periodized program resulted in approximately a 34% and 25% one RM strength gains in the squat and bench press, respectively. The percent gains shown by the other two training groups were also quite different between the bench press and squat. Further, it took longer for the periodized training to show a significantly greater strength increase over both training programs in the squat compared to the bench press. Looking at the results for the squat and bench press highlight some important ideas that are often times lost. First, for significant differences between training programs to be demonstrated, if they exist, sufficient training time must be allowed. It is very easy to show non-significant differences in training programs if the total training time is short (e.g., six to eight weeks or less). Second, the magnitude and pattern of strength gains will not be the same for all exercises or muscle groups even if the same training program is performed. So it is unrealistic to expect the exact same percent increase in maximal strength in all exercises included in the same training program. As a result in this study, the magnitude of the strength increases between the bench press and squat were quite different and how long it took before the periodized program showed significantly greater increases in strength compared to the two non-varied programs was also different between the two exercises.

THE FINAL ANALYSIS... STRENGTH/POWER PERIODIZATION

Building strength is not easy. Building muscle is even harder. But the bottom line is, there exists real concrete scientific evidence, in addition to mounds of anecdotal evidence, concerning what you can do to break through plateaus and reignite further strength increases by following a classic strength/power periodized resistance training program, such as the one I've outlined. Keep in mind, though, the results will not come overnight, especially for an experienced weight trainer, but classic strength/power periodized training should give you the consistent, incremental progress you are looking for.

References

American College of Sports Medicine. Position Stand: Progression Models in Resistance Training for Healthy Adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Medicine 34 (2002) : 364-380. Fleck, S.J., "Periodized Strength Training: A Medical Review," Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 13 (1999) : 82-9. Rhea, M.R., and Alderman, B.L., "A Meta-Analysis of Periodized Versus Nonperiodized Strength and Power Training Programs," Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 75 (2004) : 413-22. Willoughby, D.S., "The Eff ects of Meso Cycle Length Weight Training Programs Involving Periodization and Partially Equated Volumes on Upper and Lower Body Strength," Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 7 (1993) : 2-8.